It is indeed curious to note that ‘legal personality of animals’ is a subject of study in jurisprudence wherein analyses and comparisons are intricately drawn between animals and humans, only to discover and conclude that animals are no legal persons at all; that most of the legal systems, including India, neither assume nor confer legal personality in respect of animals.

Before the irrational and apparently whimsical basis behind the current scenario is dissected, some light must be thrown on what is meant by ‘legal personality’.

In simple terms, and amongst other things, the expression refers to an entity that is the subject holder of legal rights and bound by the correlative legal duties—the correlation as given and understood through the Hohfeldian thesis1. Natural persons, that is, normal human beings, are the prime claimants of legal personality because of certain inherent traits, viz, the will and capacity to act on their own, power of expression etc. So, regarding these natural persons, that is ‘us’, the legal systems throughout the world have no issues at all in assuming legal personality. This is the non-controversial position with respect to legal personality.

We, being the fortunate keepers of certain traits unique to mankind are legal persons ab initio and per-se. Law does not have to confer personality on us, unlike in the case of an idol2 , an unborn child3 and a corporation4 . The latter are the examples of a few entities that require concession5 in the form of conferment or grant of personality as certain theories of legal personality have put6 . In these cases, in the name of legal reasoning and administration of justice, law employs a certain fiction and grants legal personality to a non-human entity. Animals however, have been consciously avoided from this category. Two reasons may be cited for this exclusion:

The first reason revolves around the popular debate that since animals—‘lower animals’ as ancient jurists would like to put it7 (as human beings are superior animals)—lack the abovementioned human traits; that animals essentially are irrational beasts which lack reasoning and logical faculties and thus the question of conferring legal personality to them does not arise at all.

The second reason being the already recognized, institutionalized and well-established-through-the-ages status of ‘lower animals’. They are/have been considered as objects and not subjects of rights and duties. They are, in law as it stands today, ‘things’ or ‘chattel’ over which we have rights and towards which we have a duty to take care. The sentiment popular with many of us is that they (animals) should be happy with their property status and stop haggling for greater concessions.

The basis of this paper is to ascertain through logical arguments and reasonable analysis the strengths and weaknesses of these two reasons, the preference being skewed in favor of the latter.

To begin with, the intellectual dementia appears particularly appalling when pages after pages are written about the unlikelihood of conferment of legal personality on animals as they lack the traits that persons-properly-so-called inherently possess. For instance, they (animals) lack rationality. Steven Wise, the Harvard Professor and one of the foremost animal law experts, in his book ‘Rattling the Cage’8 also succumbs to the same consciousness when he argues in favor of granting personhood to at least certain non-human primates who are evolutionarily closest to ‘us’. This obsession with taking and treating human likeness as the basis for granting personality to animals is beyond reason. If attribution of legal personality can be purely a work of fiction (as in case of an idol, a corporation or a charitable fund etc), why can’t the same logic, if any, be applied in case of animals as well? Why is it that one tends to grope for a human link and akin-ness when it comes to ‘lower animals’? Animals are different from human beings, but, can they be disallowed something simply under the ostensible garb that they do not exhibit complex reasoning and superior intelligence? When other entities have been conferred with personality without being judged on this criterion, why is it that a special need is felt whenever the case of granting legal personality to animals is put forth?

It is worth noting that there does not exist any point of commonality between the non-human entities that have been granted personality by the Indian Legal System for various purposes. Paton, infact, asserts that the quest to discover any common essence which unifies all the entities on which legal personality has been conferred itself is outside the scope of jurisprudence; perhaps because there is no common thread running through these entities9.

Another rather amusing fact is that none of the legal theories concerning personality10 , manage to explain why certain entities are treated ‘as if’11 they are persons—why only those entities and not others; for instance, why idols, corporations and funds and not animals?

Since theories fail to explain the ‘why’ and the jurists also suggest that the query is beyond jurisprudence, it would be safe to assume that as of date, animals, to be treated as legal persons, do not have to fulfill any particular/common criteria.

Idols, corporations and funds do not bear any direct resemblance to human beings, yet they are legal persons on one pretext or the other; while animals have been consistently denied the status—why?12 This question is a bit difficult to answer but can and must be attempted nonetheless, as it might be academically relevant. If some logic is applied to reality, ‘convenience’ seems to be the only criteria that has been and is followed in granting legal personhood to certain non-human entities.

The apparently popular subterfuge that has been traditionally employed to deny personality to animals is their lack of human trait/s. This argument or ‘logic’ has been rendered hollow already (see above). Now, we come to the real reason/s behind the legal indifference/denial.

The reasons are as follows:

(a) It suits us to deny them personality: For after all, other non-human entities have been given personality because the State stands to gain/benefit revenue-wise or management-wise (for instance, in case of an idol and corporation respectively). In case of animals, granting them legal personality would entail humungous legislative efforts and require colossal post legislative management of implications. In the absence of any apparent gain, it is convenient for us to tread the beaten path and take them as objects and not subjects of legal rights.

It must be put here that though re-defining and re-structuring the concept of property and legal persons would require incremental and grand-scale changes in the existing law, does this mean that we should be opposed to improving the lot of other species with whom we coexist and who also have a claim over the planets’ resources? It is for us—the superior species, to come up with a responsible answer to this relevant question.

(b) In order to retain our superiority: Another reason behind our denial and indifference could be that it gives us a chance to gloat over and reinforce our superiority and age-old dominion over animals. Treating animals as property has so deeply ingrained the human consciousness on account of centuries of undisputed and uninterrupted rule over animals that humans have become averse to even reasonable improvements of their lot, for the fear of being dislodged from that elevated pedestal.

Denying legal personality to animals ensures our dominion over them and gives us a freedom to maltreat them, without inviting much penal sanctions13.

Also, if personality is attributed to animals, they are likely to evoke and invoke greater societal/community sympathy in court battles. So, we fear that once made equal to man (human beings as such), by the power of legal personality, they (animals) might become a threat to our status.

Regarding this point, it is necessary to mention that the intention is not to counter the notion of ‘superiority’ that human beings have been nurturing since times immemorial; for it would mean asserting something absurd against the inevitable. On this planet and at least to date, Homo sapiens remain the undisputed superior. In what respects they are ‘superior’ needs no elaboration and thus, should be considered as understood.

Humans have immense power as a species and what needs to be understood is that with great power comes great responsibility. It is for us, who claim to be superior, to guard the interests of other species. Convenience (in not granting legal personhood to animals) must be abandoned in favor of compassion and humanity—a virtue truly unique to mankind and alien to beasts. Laws should also reflect this aspect. Presently, though animals have been accommodated in many respects, by and large the legal regime remains primarily for the benefit of human beings. The legislations14, proceed on the notion that only those animals deserve protection, which are either useful or amusing to human beings.

It is asserted that we can grant legal personality to animals through fiction while retaining our superior status at the same time, if the tag is all that relevant.

To conclude this point, it is understood that legal personality cannot be taken as attributed to non-human entities in the same sense and degree as it is assumed in case of human beings/natural persons, because the nature of the two differ drastically. Thus, animals also need not display any human traits or akin-to human-characteristics to be eligible for legal personality (as emphasized elsewhere in the paper).

Similarly, just as corporations have only as much personality as the law imputes to them by fiction; it is possible, by all means, to attribute a restricted personality on animals as well15. They can have some measure of personality, just sufficient for them to eke out a decent survival amidst the human sea; just enough to ensure that their interests are not intentionally ignored, maliciously trampled and consistently abused. The personality so attributed should allow them to vindicate their rights against the superior species, that is, ‘us’.

(c) Warped understanding of the concept of standing: Another reason, the third one, on why personhood has been consistently denied to animals is because of a warped understanding of the concept of standing.

It is often believed and argued by a set of people that granting legal personality to animals would be legally impossible or meaningless at any rate, as they would not be able to assert the rights so granted in the court of law. It is true that animals cannot generally be plaintiffs in a lawsuit, but since when did membership to particular specie become a criterion to institute lawsuits? Both an idol and a fund16 require human agents to carry out the activities incidental to litigation. Why can’t then such an agent be employed to vindicate animals’ rights?17

Another issue related to standing is that the grant of legal personality would result in one animal asserting against another animal (i.e. person) the right to, say, live! This can be tackled easily, and infact would be taken care of automatically, if the personality attributed to animals is restricted in the sense explained in the above paragraphs—that is, by confining attribution in such a sense that rights can be asserted primarily against human beings, them being the major unnatural and avoidable interference to their survival18.

If a mathematical formula is introduced into jurisprudential reasoning, then to say that grant of personhood to animals would result in one animal filing a lawsuit against the other sounds absolutely logical and inescapable. But, the point is that law is not all mathematical logic, it has to be reasonable as well. Reasonability suggests that one would have to ignore and exclude inter-species brutality of the animal world from the purview of legal personality. In short, the legal system would have to devise ways and chart out an arrangement whereby the interests of social and lower animals are harmonized. Even if law remains primarily for human beings, which in all likelihood it would, but manages to accommodate animal interests optimally and honestly; it would be a laudable effort. Taking an extreme view in this regard would be catastrophic, no doubt.

(d) Age old emphasis on legal duties: Fourth reason why animals have been denied legal personality by the legal systems is the age-old emphasis on absolute duties19.

Austin suggested that animals cannot be holders of rights and duties—they are entities towards which human beings, owe an absolute duty. These are duties that do not have any correlative advantage in the form rights in others corresponding to them.

Though when he gave the concept of absolute duties, he did not have legal duties in mind , yet, in the modern era, many such duties have been pulled into the legal net by being elevated to the status of legal duties. In-so-far as the Indian Legal System is concerned, all the anti cruelty provisions and statutes concerning animals are an open manifestation of these legal duties. However, they are legal duties for the benefit of animals and not towards animals in the strict Hohfeldian sense. This is because the corresponding legal right is not held by animals in these cases. The repository of that legal right is some other representative entity through whom the benefit would ultimately flow in favor of the animals (as would be seen later through a tabular analysis on the basis of the Hohfeldian thesis).

So, those who are fixated with this concept of duties towards animals continue to deny them acceptance as entities worthy of possessing legal rights.

It is certainly laudable that humankind has acted responsibly by legalizing certain duties that benefit animals by instituting anti cruelty provisions, but such attempts at revolutionizing social values concerning animals need teeth to be effective. Grant of legal personhood would entail making animals’ subjects of legal rights and duties and would enable the social revolution gather the requisite momentum.

(e) Opiniated mindsets: The final reason that may be cited on why animals have been denied legal personality is related to the fourth and it is: opiniated minds.

Every time the legal system is on the threshold of a renaissance in expanding the kitty of non-human legal persons, we tend to throw up reasons on why it is feasible not to do so. This blind aversion curbs all legal improvisation. This is also the reason why animals have failed to get their status altered from property to persons.

Before this paper reaches its conclusion, it is important to put in a few lines about the current status of animals in the Indian legal system. It appears necessary because certain issues like ‘anti cruelty laws’ and the penalty provisions tend to create confusion and spread the notion that animals are already the holders of legal rights, in the sense that they have a legal right not to be treated in a cruel manner. If we follow the Hohfeldian thesis, we would realize that it is not so. For the sake of understanding, the statutes/legislations that speak of directly/indirectly preventing cruelty towards animals or protecting animals have been classified.

They are:

(a) The Criminal laws, which, in the case of India, would primarily be the Indian Penal Code 1860: the main substantive criminal legislation of the country;

(b) Tort Laws; and

(c) The Special Statutes like the Prevention of Cruelty towards Animals Act 1960, the Wildlife Protection Act 1971 et al.

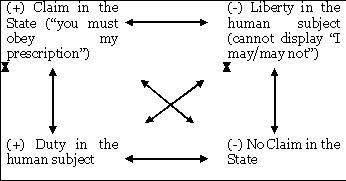

If cruelty against animals is a provision under the Criminal Laws, animals are not the repository of legal rights—the State is:

Since State is the sole master of criminal prosecution, one party, in any criminal matter, has to be the State. The State, hence, has the legal right to demand adherence to its prescription. It can display the behavior ‘you must’—that is ‘You must follow my prescription’. Against this, subjects are under a correlative and corresponding duty to abide by the prescription.

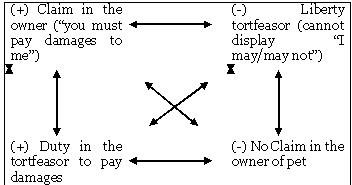

If cruelty against animals comes under the Law of Torts, then, in all probabilities, the tortfeasor owes a legal duty (to pay damages) towards the owner of that animal (in case of a pet animal). The owner can display the behavior ‘you must’ that is, ‘you must pay damages to me on account of the injury suffered by me via my animal/pet. The table would be as follows:

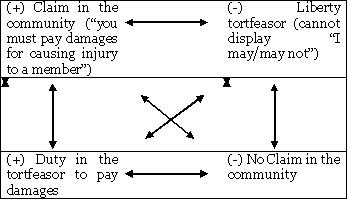

If however, the animal is a stray, the community at large may be said to have a legal right to vindicate the stand of the stray animal, which, according to Salmond should be treated as a member of the community as a whole21. The table in this case would be as follows:

Claim in the community may manifest through public interest litigations as has been well established in India through the case of Shriram Fertilizers (1987-SC)22

It is worth noting that in all the three tables above, no legal duty is owed towards the animal as such, and there vests no legal right in them.

Coming to the special laws—Art 48A of the Indian Constitution directs the State to make efforts towards protecting and improving the environment and safeguarding the forest and wildlife of the country23. The abovementioned special laws are a result of those efforts only. Under these laws, the parent Act itself has appointed an administrative body to carry out the purpose of the legislation. Thus, there vests a legal right in that authority to demand adherence to a particular conduct corresponding to which there exists a legal duty in the public at large to do or abstain from doing something.

To sum up, we do not owe any legal duty ‘towards’ animals. In other words, they are not holders of legal rights, for that is a privilege exclusively reserved for legal persons.

The widespread notion is that by strengthening the anti cruelty laws, animal rights would become meaningful. This is not true, as animals, in this country at least, are not the repository of any legal rights. If laws enacted to prevent abuse and cruelty are strengthened, the animals do stand to benefit, no doubt, but they do not stand to take even a small step towards legal personhood. At the most, these anti-cruelty legislations reflect the extent to which humankind has been willing to accommodate the lower species or the extent to which it has agreed to put restraints upon itself.

To conclude, the question whether animals should enjoy legal personality or not needs to be answered in the affirmative. With a lot of good work being done to improve the living conditions of animals (working or wild), the time is just ripe for these not so social animals to demand some substantive gains. In order to foster a change, we not only require a compassionate Legislature, but also need to overhaul certain viewpoints through a social revolution and an open minded judiciary.

Finally, those who still discard the idea of granting legal personality to animals as musings of a dreamy academician, fit only for class-room teaching, there is only one thing remaining to be said: “Some minds are like concrete: thoroughly mixed up and permanently set”.

References:

1. The analysis of rights in the wider sense (as referring to rights strictu sensu, liberties, immunities and power) and the correlatives reached its culmination with the work of Hohfeld. See his ‘Fundamental Legal Conceptions’, published posthumously in 1923.

2. See Pramatha Nath Mullick v Pradyumna Kumar Mullick [1925] LR 52 Ind App 245, discussed by PW Duff, 3 Camb LJ (1927), 42.

In this case, it was put that ‘the will of the idol in regard to the location must be respected’. Normally, this will would be interpreted by the guardian but the law would interfere if the guardian did not act in the interests of the idol, that is, presumably after consulting the interests of the worshippers.

3. For instance, section 20 of the Hindu Succession Act, 1956 lays down that a child who was in the womb at the time of death of the intestate and who is subsequently born alive, has the same right of inheritance, as if he was already born when propositus died, This, the unborn is the subject of legal rights.

4. ‘Besides men or natural persons, the law knows as subjects of proprietary rights, certain fictitious, artificial or juristic persons, as one species of its class it knows the corporation’: Savigny.

‘Corporations are invisible, intangible and existing only in contemplation of the Law’: Lord Coke in

5. As for the concession theory, see ‘A Text Book of Jurisprudence’, by George Whitecross Paton, (4th Edn) pp 411-413.

6. For theories of legal personality, see ‘A Text Book of Jurisprudence’, by George Whitecross Paton, (4th Edn) pp 407-419.

8. See ‘Rattling the Cage, Towards Legal Rights for Animals’ by Stephen M Wise, Perseus Books ISBN: 0-7382-0065-4.

9. See ‘A Text Book of Jurisprudence’, by George Whitecross Paton, (4th Edn) pp 408-409.

10. As for legal theories, see ‘A Text Book of Jurisprudence’, by George Whitecross Paton, (4th Edn) pp 407-419.

11. See‘Jurisprudence’. RWM Dias (5th Edn) p 268.

12. Paton also appears to agree when he says that ‘legal personality refers to a device by which the law creates or recognizes units to which it ascribes certain powers and capacities…..it says that certain things shall be units for the purpose of the law and that such unit shall possess the capacity of being parties to the claim-duty/power-liability relationships’.

Thus, the basis of conferment, the ‘why’ part has been safely omitted by law. The deliberate omission of animals from personhood becomes clear when Paton (though in a different context) says that ‘though it might sound absurd, but it is not impossible for the law to accord legal personality to trees, sticks or stones’.

13. See the Indian Penal Code 1860, ss 428 and 429.

14. As we would see later in this paper.

15. See A Text Book of Jurisprudence’, by George Whitecross Paton, (4th Edn) p 393.

16. . These entities are recognized as legal persons for different purposes by the Indian Legal System.

17. The author emphasizes that it is not the lack of standing for assertion of legal rights that would be a consequential problem (if any problem arises at all post the grant of personhood to animals), but it is inability of animals to fulfill legal duties (or the inability of the representative human agent in making the Principal discharge its legal obligations) that might pose some difficulties.

18. For jungle beasts, killing or attacking each other to satisfy their hunger and establish superiority through display of brute force is something natural and thus, unavoidable—our legal system needs to ‘factor-in’ this aspect, while granting legal personality to animals.

19. See ‘Legal Duties’ by CK Allen, p 156; see also ‘A Text Book of Jurisprudence’, by George Whitecross Paton, (4th Edn) p 294.

20. See ‘A Text Book of Jurisprudence’, by George Whitecross Paton, (4th Edn) pp 294-297.

21. See ‘Salmond on Jurisprudence’ (12th Edn) p 300.

22. See MC Mehta v Union of

23. See the Constitution of India art 48A.

No comments:

Post a Comment